BRIDGES Cologne Participates in 2025 Global Solutions Summit in Berlin: Reflections by Dr Nsah Mala

From 5-6 May 2025, BRIDGES Cologne participated in the 2025 Global Solutions Summit (#GSS2025) in Berlin (Germany) through our Hub Director, Dr Nsah Mala. Fondly referred to as the World Policy Forum, the Global Solutions Summit brings together diplomats, businesspeople, politicians, policymakers, civil society organisations (CSOs), students and youth, researchers and scholars to discuss global challenges and explore or suggest potential solutions to them.

According to their website, “The annual Global Solutions Summit is an international conference aimed at addressing key policy challenges facing the G20, the G7 and other global governance fora. It assembles those who believe that the future can be successfully shaped through global collaboration grounded in mutual respect. Together, we strive to find actionable solutions to shared global challenges.”

This year, the #GSS2025 was held under the theme “Bridging Divides: New Pathways for Global Prosperity”. The 2025 Summit brought together about 1000 guests from over 100 countries in more than 30 sessions in two days, discussing solutions to current global challenges. In this regard, “All sessions and encounters [explored] how to defend, expand, and re-invent multilateral structures to promote human flourishing and meet the challenges of the twenty-first century.”

In the rest of this blog post, Dr Nsah Mala (born Kenneth Nsah), from the University of Cologne, who was invited to the Summit, will share his experience of attending #GSS2025 and how it connects to the thematic focus of the BRIDGES Cologne Hub for Planetary Wellbeing within the UNESCO-MOST BRIDGES Coalition.

In her opening keynote for day 1, Dr Alaa Murabit – an award-winning global security strategist, women’s rights advocate, and medical doctor – enjoined the world to embrace bold leadership in order to find equitable and locally-driven solutions to global challenges while prioritising resilience, agency, and justice. Apart from advocating a move from performative action to delivery, she also called for solution designing that allows for regeneration, and the holding of space for emergence. She also stressed the importance of leadership that is not about protecting integrity (or dignity) but using dignity and integrity to create impact. Recognising, disappointingly, that less than 12% of climate finance reaches front line actors, Dr Murabit made a clarion call to action: We must shift resources to those in the most need, not as charity but as strategy. Where trust and agency are allowed to flourish, she noted, there is transformation.

Another keynote that stood out for me was that of His Excellency Macky Sall – former President of Senegal and former President of the African Union (AU) – which opened day 2. As I have noted elsewhere, among many other things, Macky Sall stressed the need to create spaces for dialogue to resolve multiple global crises such as conflicts, trade wars, climate change, and obsolete multilateral mechanisms. Furthermore, he underscored the importance of ensuring peace and security in Africa and the necessity to undertake reforms of post-WWII global institutions (both political and financial) to respond to Africa’s aspirations. He also highlighted how Africa’s economic development must be premised on agriculture, value addition to African raw materials, and harnessing the demographic advantage of a youthful population. Macky Sall rightly pointed out that what Africa needs is neither foreign aid nor charity, but fairness and equity in international trade. In other words, foreigners must be prevented from their exploitative tendencies towards Africa.

In terms of climate action and climate finance, Macky Sall repeated Africa’s call for justice given our relatively small contribution to the climate crisis. As a matter of fact, Africa contributes the least to climate change (less than 4% of global emissions) but suffers the worst climate impacts, while offering great ecosystem services and nature-based solutions. Macky Sall also mentioned Africa’s numerous natural resources and rich rivers like the Congo.

After his keynote, I had a brief chat with Macky Sall. I emphasised the significance of the Congo Basin and pointed out the importance of aligning Africa’s development with the future generations agenda and long-term approaches anchored on strategic foresight and collective intelligence, according to the UN Pact for the Future. Sadly, throughout the Summit, I only heard the UN Pact for the Future mentioned by one person, Melanie Hauenstein, Director of the UNDP Germany Representation Office. She mentioned the UN Summit of the Future and Pact for the Future and Hamburg Sustainability Summit during the panel on “Economic Inequality.”

Besides keynotes such as the two discussed above, I took part in many interactive sessions and panels. In the geopolitical domain, I witnessed sessions on “The Changing Landscape of Multilateralism: Navigating Global Power Shifts,” “The Future of the G20 in a Changing World,” and “US Perspectives on Global Leadership before the 2026 G20.” In terms of economic development, I attended two sessions discussing “Flourishing-Centred Growth and Development Model” and “Economic Inequality: A Systemic Risk to Global Cooperation.” In the domains of energy, decarbonisation and industrialisation, I participated in the following sessions: “Green Industrial Policy as a Driver of Economic Transformation,” “Geopolitical Challenges to Industrial Decarbonization,” “Geopolitical Challenges to Industrial Decarbonization,” and “Just Energy Transition and Decarbonization.” Relatedly, I attended a session that explored “Africa’s Energy Transition” in terms of Access, Resilience, and Prosperity. Moreover, I took part in a session on “Future-Proofing Food Security for Resilient Societies.”

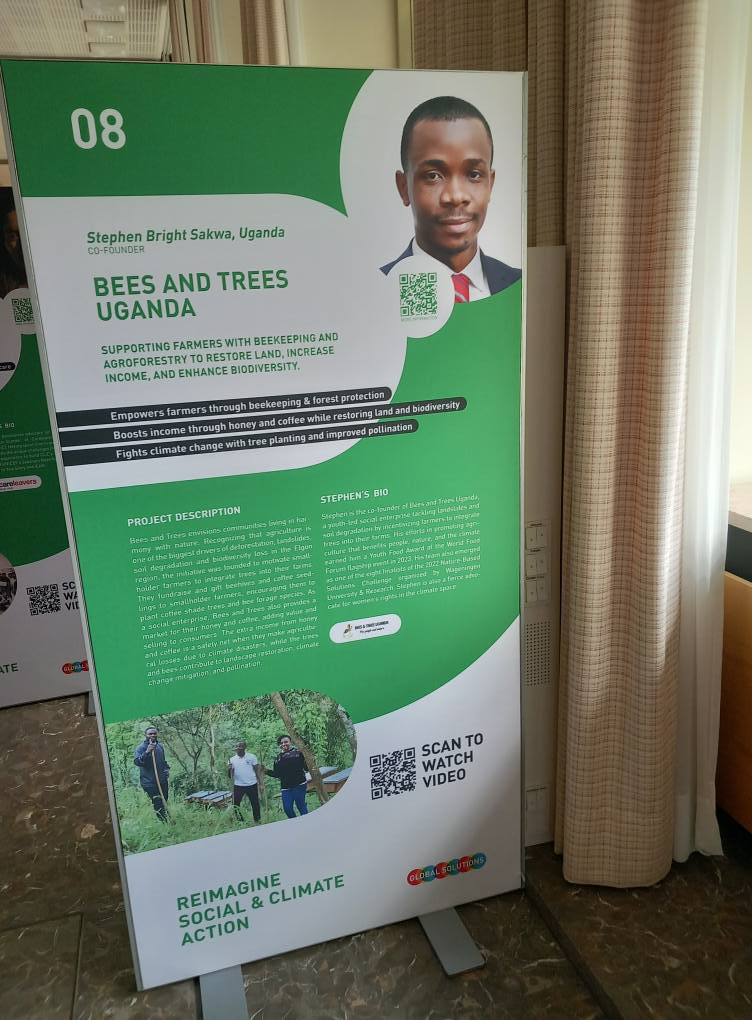

Another major highlight of #GSS2025 was the Young Global Changers (YGC) programme, launched in 2017 and bringing together a diverse group of young innovators who are committed to transforming economies and societies for a more sustainable and equitable future. The YGC programme includes the annual YGC Recoupling Awards, recognizing outstanding projects across three categories: reimagine business, social and climate action, and civic engagement. As part of the YGC Recoupling Awards fifteen shortlisted young people showcased and pitched their innovations, which included (among others): using AI and solar energy to monitor crop health in Kenya; tackling menstrual poverty in Brazil; beekeeping for pollinating trees and sustainable agriculture in Uganda; establishing local governance bodies, securing tenurial rights, and promoting sustainable livelihoods and health in Indonesia; empowering young people to rebuild their democracy and create a better kind of politics for future generations in Australia; and tracking electoral promises to provide citizens with the tools and information they need to hold elected officials accountable in Nigeria.

In the panel on “Geopolitical Challenges to Industrial Decarbonization,” for instance, Amar Bhattacharya, from Brookings Institution, suggested that local action can produce global public goods. That is, renewable energy uptake at local level leads to global climate action and decarbonisation. Thus, we should see challenges as opportunities, remembering that massive investments are needed in clean energy in the Global South. Amar enjoined stakeholders to go beyond the World Bank’s mission of providing energy to 300 million Africans, bearing in mind that Africa holds about 60% of global solar potential. In the same panel, on her part, Isabelle Durant, former MP and Deputy Prime Minister in Belgium, reflected on how we can find a balance in developing countries between cement, steel and iron as higher emitters of greenhouse gases and their need for infrastructural development. She also stressed the need to relax intellectual property rights in favour of the Global South in terms of clean and green technologies; the necessity of investing in clean cooking in Africa thus leading to enormous health and environmental benefits; and the need for new rules and fairness in access to finance for climate and development. Accordingly, she acknowledged enormous difficulties for talented African youth and women to access finance for green development.

In the session on “Africa’s Energy Transition,” Dr Miriam Omolo, from the African Policy Research Institute (APRI), suggested that African countries can mobilise local finance for renewable energy through taxation, investors, and philanthropy. But she cautioned that they should not start with philanthropy. And she made it clear that Africa needs political will and good leadership that promotes predictable business environments before bringing in philanthropy. Dr Omolo noted that venture capital is good but often wipes off local visions and skills for youth. She acknowledged that some energy projects stall because they displace many local communities. Furthermore, she stressed that the DRC and Congo Basin have critical minerals, which are sadly a source of conflicts due to vested foreign interests. She also underscored the need to invest in African youth who are good in IT innovation and the need for African countries to do power pulling and supply their neighbours, building on the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) to trade in renewable energy. Elsewhere, in the session on “The Changing Landscape of Multilateralism,” Dr Philani Mthembu, from the Institute for Global Dialogue, suggested that there is no going back to a pre-Trump 2.0 aid-based world because a fundamental shift is happening and we should continue to learn to adapt. In this regard, Dr Mthembu highlighted the enormous opportunities Africa stands to create through the AfFCTA, which is going to become the largest market in the world.

Meanwhile, in the same session on “Africa’s Energy Transition,” Lauren Hermanus, from Southern Transitions, pointed out how Africa is expected to perform almost a miracle given that no region in the world has industrialised without destruction of the environment, especially in terms of dirty energy (fossil fuels). As Hermanus pointed out, Africa is essential to global decarbonisation but is only currently used as a source of low-cost critical minerals. She shared the sad story of Guinea (in West Africa), which holds 25% of global bauxite, but remains very poor – a story that is true of many mineral-rich African countries. As she narrated, an additional layer of sadness and injustice for Guinea is that each foreign company extracting bauxite has its own railway leading to its port, but Guineans do not have access to the railways! Furthermore, Hermanus noted that very few of the 54 African countries have enough critical minerals to leverage market power in negotiations. As a result, she did not only call for the transformation of international cooperation and partnerships, but also stated that people based in Africa must be empowered to make good asks and bargain well, not in isolation. In this regard, on my own part, I wondered if Africa may not consider forming a group of African Negotiators for Critical Minerals following the example of the African Group of Climate Negotiators (AGNES). I wanted to make this suggestion during the question-and-answer slot but time did not permit me.

Still in the same session, on his part, Dr Fabio Cresto Aleina, from Global Citizen, echoed other speakers in acknowledging that Africa receives less than 1.5% renewable energy financing. He underscored the importance of crafting and disseminating new and positive narratives that can drive financial support for Africa. In other words, there should be a shift from negative narratives of energy poverty to positive narratives of energy potential and resilience.

There are many connections between the Global Solutions Summit and the thematic focus of BRIDGES Cologne Hub for Planetary Wellbeing. Both the UNESCO-MOST BRIDGES Coalition and the Summit (including the 2025 edition) are committed to addressing complex global challenges, especially in alignment with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and now the UN Pact for the Future. As I always say, sustainability and planetary wellbeing (for both present and future generations) are two sides of the same coin. That said, #GSS2025 in particular chimed very much with planetary wellbeing as evidenced by many sessions and panels and even keynotes which addressed issues such as multilateral reforms, energy transitions based on justice and renewables, economic inequalities and going beyond GDP, food security and human flourishing. However, apart from the occasional mention of culture, context and narratives which are core to our humanities-inspired work at BRIDGES, the Summit speakers were quite often too human-centric and silent on Earth-centred issues such as biodiversity, indigenous knowledge, interdependence, and justice, which are fundamental to scholars in humanities and social sciences.

For example, in the insightful and enriching session on “Green Industrial Policy as a Driver of Economic Transformation,” the speakers pointed out that the clean energy transition is no longer a burden but an opportunity. Yet, emissions are still climbing alarmingly! In the words of Izabella Teixeira, former Brazilian Minister of the Environment, we are witnessing more energy addiction than energy transition today across the world as fossils are hardly replaced. Izabella also shared the inspiring example of Brazil which produces 90% of its energy grid from renewable sources. And there is a Brazilian company that produces non-fossil fuel for aircraft. Nevertheless, overall, I noticed that the discussions in this session were narrowly focused on reducing emissions and which relevant business models to adopt. Accordingly, during the question-and-answer slot, drawing on my humanities and BRIDGES background, I asked the speakers two questions in terms of (1) the negative impacts of clean energy on biodiversity and ecosystems and (2) issues of injustice such as the forceful displacement of local and Indigenous people for green energy projects. My questions were very well received and nearly all speakers and even the moderator recognised their importance by offering satisfying answers.

Similarly, the session on “Future-Proofing Food Security for Resilient Societies” was very insightful and inspiring. For instance, Professor Ousmane Badiane, from AKADEMIYA2063, discussed how they are using Africa Agriculture Watch (AAgWa), for predicting harvests and tracking 10 crops in over 40 African countries, as well as tracking land use, ecosystems, and forest cover, thanks to artificial intelligence (AI). According to their website, “Launched in 2021, Africa Agriculture Watch (AAgWa) is a web-based platform that employs cutting-edge machine learning techniques and satellite remotely sensed data to predict agricultural yields and production levels of several crops across Africa to support decision-making, monitoring, crisis management, and effective intervention planning in local communities.” Meanwhile, Professor Hamadi Boga, from Alliance for Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), discussed the importance of avoiding food waste through post-harvest preservation given that there is too much food wastage. He also underlined how AI can be leveraged in monitoring to improve food security. Obviously, this point connects very well with AAgWa and one of the YGC Recoupling Awards projects from Africa (Kenya) that focuses on using AI in agricultural pest monitoring and control.

While lauding Professors Badiane and Boga for their inspirational initiatives, including the use of technology, in favour of food security, I asked a question aimed at knowing what they are doing to ensure posterity for indigenous knowledge and seeds for food security. In the responses from Professor Boga and Máximo Torero (from FAO), it emerged that the Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) and partners are working on an initiative at the Shamba Centre for Food & Climate called Vision for Adapted Crops and Soils (VACS) with the aim of supporting African farmers, civil society organisations and governments to face the challenges posed by climate change to the region’s food systems. One of the aspects of VACS consists of organising workshops “to gather knowledge and views on how indigenous crops can improve nutrition, dietary diversity, and climate targets in Africa.” In his own response, Professor Badiane discussed how they could potentially combine geospatial skills to track indigenous varieties of plants and their nutritional values and study soil characteristics and then integrate them into mainstream agriculture practices for food security.

Furthermore, in the same panel, Mapule Maema, from Economic Justice Network in South Africa, discussed intersectionality in terms of food security as well as collaborating with grassroots organisations that work directly with farmers, while keeping youth, gender, transportation, urbanisation, etc. in mind. Despite her focus on intersectionality and justice, it seemed to me that her intervention was narrowly human-centric with less focus on biodiversity and planetary dimensions. Accordingly, once more with my humanities background, I asked a question on the importance of biodiversity for food security, citing the Amazon and Congo Basins, which are well known for their biodiversity and injustices on indigenous people.

In conclusion, I would argue as follows: Despite the satisfactory answers that speakers provided to my questions and those of other participants with similar questions, it is clear that such gatherings as the Global Solutions Summit need the active presence of more people from the humanities and social sciences and institutions such as BRIDGES who will constantly bring certain issues to the fore. These issues include biodiversity, indigenous and local knowledge, the importance of narratives and cultures, spiritual dimensions, and so forth, which all align with Earth-centred and planetary approaches to addressing global challenges. Instead of focusing on economic and human flourishing alone, we need more emphasis on planetary wellbeing and ecological flourishing which are the bedrocks for any other form of flourishing and sustainability for present and future generations.